Yesterday, a familiar photograph popped up on one of the UH-60 Facebook pages I follow – old professional habits never truly die. At first, I was irritated that one of my pictures was circulating without credit or explanation; however, rather than be petty, I saw it as an opportunity to write from experience:

NTC 1999. Source: author

Just to be clear, I am not salty about this picture resurfacing… my only issue is that when these things get posted by a third party, the facts are often omitted/mangled and a possible teaching point can be misrepresented.

This was in NTC in 1999. I would love to tell you when, exactly, but I was stationed with B Co. 9/101 and we went to NTC enough times that the trips blended into one long, miserable mess. There is a good chance that this was one of the first rotations – we banged up a lot of birds in 15 days.

For those who guessed “dust landing with excessive aerodynamic breaking and too much aft cyclic,” you are correct. We came in faster than normal after taking a couple Engineers around our old AA to check for holes to fill after we jumped.

This was NOT a hard landing… the tail wheel encountered a small mound which popped the tail up just enough.

The ALQ was not seriously damaged – the trailing edge of all four M/R blades had a neat pair of grooves from the screws on top of the ALQ, but other than two tip caps and the driveshaft cover/gear box damage you see, everything else was fine.

The errors made by everyone in this event (myself included) were:

Landing speed too fast for the environmental conditions…

Poor habit transfer from roll-on landing training on runways…

Lack of advocacy and assertion (speaking for myself) – I recognized the problem but had entirely too much faith in our CW3 IP…

Crew rest policy – the backseaters were on day #16 of straight operations and I will honestly say that I was worn out at that point with jumping every two or three days, operations, and environmental issues…

Again, I love seeing photos with solid and teachable stories behind them… Perhaps those lessons will resonate so they won’t be cyclic.

Of course, there are more pictures which are part of the larger story…

Intermediate gearbox cover and section 3 driveshaft cover… Source: author

View from the right side. Source: author

View from the left side. Source: author

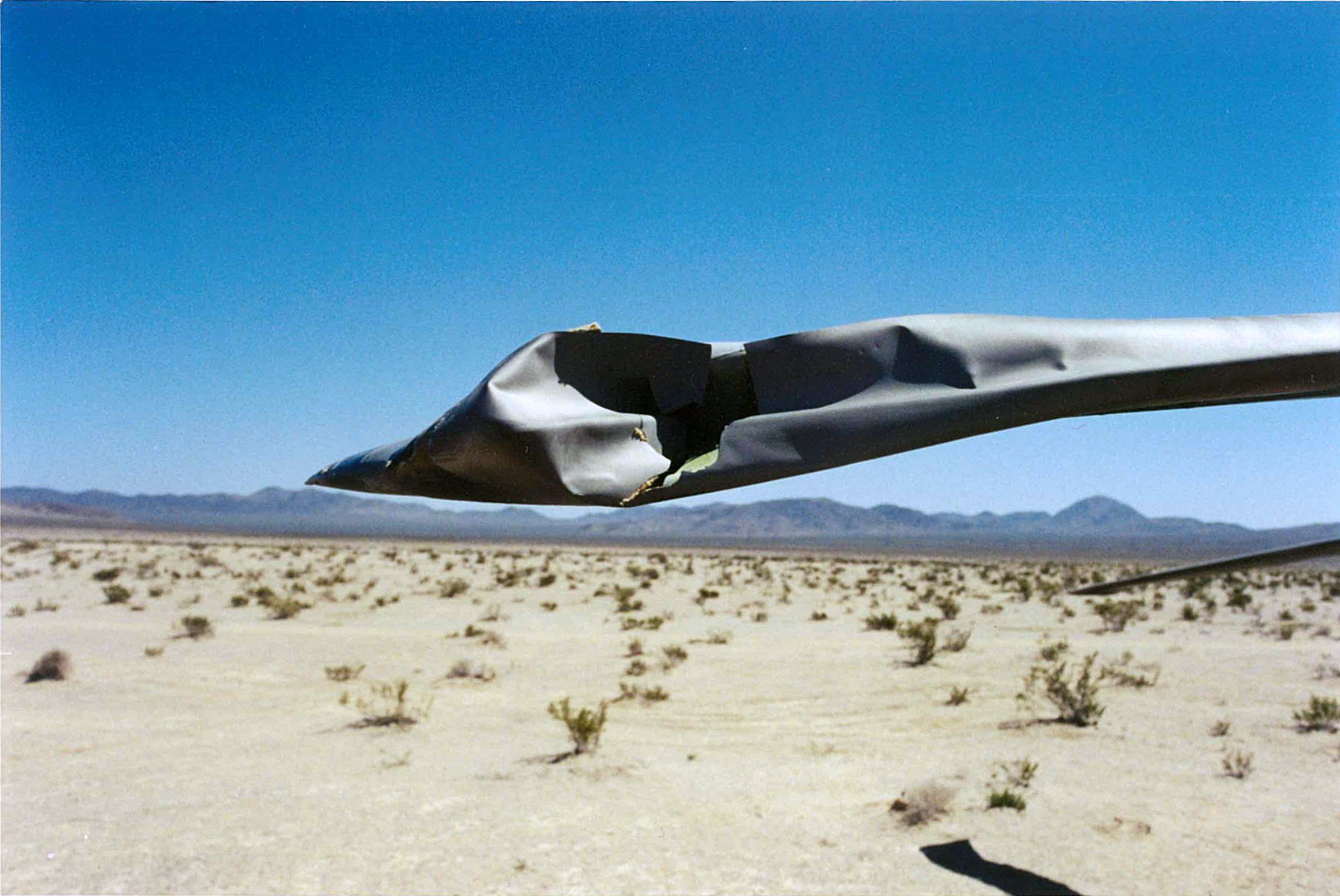

The first of two damaged tip caps. Source: author

The second of two damaged tip caps. Source: author

Yours truly… NTC 1999. Source: author

The last picture offers a good indication of the terrain we routinely contended with and which contributed directly to this event… The various mounds probably caused enough flexing and movement to create the perfect circumstances for the main rotor blades to contact the tail; the small mound behind the tail wheel corresponds roughly to the moment we felt the first impact.

The worst lesson is the one which isn’t heeded. Because of this event, I took a long hard look at myself and my role in it. I spoke up more, I communicated a bit better, and I started to pay more attention to the organizational attitudes and norms I had previously disregarded. No one is perfect, and I will not stretch the truth to imply that my actions following this incident were impeccable. However, what I did learn about crew coordination and communication that day stuck with me.

Over the years, the U.S. Army has invested time and resources in developing a formal and standardized approach to the interaction among aviators to facilitate safe operations in a high stress/high reliability environments. This process, like other civilian efforts, is one which is continually evolving as trial and error sorts out which has historically worked from that which hasn’t.

Regardless of where in the overall timeline of crew coordination one looks, certain absolutes become apparent; in this case, one of my favorites became very clear – advocacy and assertion. I say this is a favorite only because of its broad applicability beyond the cabin and cockpit. Loosely defined for this context, advocacy is a firm recommendation towards a favorable course of action, while assertion is knowing what is right/safe and not wavering from advocating an action accordingly.

Dust landings are no joke, regardless of one’s experience levels. Compounded by the lack of a reliable visual horizon is the sudden unreliability of one’s own vestibular system as the helicopter rapidly changes attitude, the illusion of movement due to blowing dust, and the loss of dimensional contrast in those first and last glimpses of the intended landing area. That last part is what eventually got us – it was difficult to determine exactly how flat the area was where the pilots intended to land. Coupled with our rushed approach speed and our overall comfort in expectations that this was to be no different than every other approach, it ended poorly, but not as bad as it could have.

Comfort, in aviation, is often the precursor to excitement. Paired with an operational tempo which could be best described as frantic and persistent, we sacrificed perceived comfort (crew rest) for mission needs… all during a training event. Years later, we all learned from the peacetime mistakes as we went abroad to Iraq and Afghanistan… only to start the learning process all over as the environment and threat changed on a daily basis.

What remains is the knowledge of the process of learning, on an individual and organizational level… and a key part of a life I can never fully leave behind.

Fly (and Drive) Safe.

Discover more from milsurpwriter

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Lack of advocacy and assertion (speaking for myself) – I recognized the problem but had entirely too much faith in our CW3 IP…”

I’ve been browsing through the USS Fitzgerald collision report, and I am shocked by the lack of objections by junior personnel to the conditions that existed. I supposed that they thought that the Chiefs and Division Officers would handle it, and so they didn’t advocate for themselves. Seven of them died.

I learned early on in my career that if I thought something was wrong, and I knew I was right, I didn’t just have a duty to speak up. I had a vested interest in staying alive to speak up.

With time and experience, I learned how to speak up with more tact and technical expertise, but always with that vested interest.

Keep writing!

-ȸ

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, the Fitz is going to keep people busy for a while…

Sadly, there is somewhat of a disturbing trend with many industrial and military accidents where someone either didn’t speak up or was dismissed due to their position on the organizational hierarchy.

Human nature, I suppose. We both know that, like warfare, there are certain aspects of ourselves we wish we could grow out of…

LikeLiked by 1 person