Over the years of writing on this blog, I have come to the realizations that I favor the ideas of theory and philosophy as well as orders of effect beyond the immediate reactions to what heats debate. This is an odd stance to maintain; my academic focus has centered on the past, my professional experience has straddled the pressing needs of the moment against the organizational goals of the next pressing issue, and my personal approach to long-term planning has been more of a “delay and preparation can lead to better options and decisions when needed” approach.

However, my mind never seems to stop bouncing from what relevance the past might bring to what the future might look like based on the trends within human history.

Out of the blue, three questions popped into my mind today – fleeting ideas which found me scurrying for a pencil and paper to capture them before they dissolved into the ether of other intangible concepts floating in my head:

“What stops China from fighting?”

“What prevents war?”

“What next?”

The first – what factors might be currently restraining China from initiating a conflict with the United States – stands as a gaping rabbit hole of research. Concepts like this are intimidating on so many levels: the economic, societal, diplomatic, industrial, agricultural, and strategic factors involved would easily shift this from a blog written as a hobby to a book-length thesis of speculation and analysis… something which would dissuade all but the most staunchly curious reader.

However, I can force myself to rely on one or two external sources to support this notion while leaving myself – and the reader – the opportunity to expand upon this idea more at a later point. One such source has become one of my favorites due to the fact that it covers so many different aspects and encourages consideration along relatively untrodden paths: National Will to Fight – Why Some States Keep Fighting and Others Don’t.

I’ve used this source before, and in related threads: Thoughts on Article 5, Consciousness and History, and Winning… in Afghanistan?. In the case of the motivating factors which shape China’s – or any other major potential antagonists’ – decisions on whether or not to commit to a full-scale conflict, this RAND publication is not only relevant, but vital in understanding the elements behind initiation and sustainment of what would inevitably be an expensive and catastrophic course of action.

For the sake of clarification, the national will to fight is defined as:

…the determination of a national government to conduct sustained military and other operations for some objective even when the expectation of success decreases or the need for significant political, economic, and military sacrifices increases. (page ix)

Essentially, the will is guided by complex “cost to benefit” analysis. In the case of China, we are presently experiencing layers of deception focused upon one prime variable: the impact of the present pandemic on their population, economy, and military readiness.

People need food, and conflicts have been indirectly traced to either a shortage of food and other vital resources for the population of a nation prior to a conflict or the desire to expand and control such resources. Whether shortages caused by weather, population explosion, or unexpected changes in production capacity, food can be a significant link in the conditions which lead to conflict.

From the 2011 paper Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict: Causes, Consequences, and Addressing the Challenges, this correlation is clear:

The mixture of hunger – which creates grievances – and the availability of valuable commodities – which can provide opportunities for rebel funding – is a volatile combination. […] as a country’s import prices increase, thereby eroding real incomes, the risk of conflict increases. (page 5-6)

Economies are closely tied to food – as state above, the ability to import and export food is related to the overall wealth of a nation in terms of trade and currency. Along with this, the access or desire to acquire resource-rich regions has provided the context for the uncontrollable spiral from diplomacy to military action. Whether it is the exploitation of recently discovered oil reserves or the instability of existing borders and nations co-located with regional or global trade routes, the ability to influence and/or directly control access and grant conditional permissions might place a nation in an advantageous position over perceived or actual threats to their economy.

Finally, military readiness unifies the importance of sufficient food and economic ability for any and all potential aggressors or defenders. As a possible justification for preparation or anticipation of a conflict, the state of a nation’s ability to respond and/or deter any forcible threats against another nations’ food or economic assets. For the sake of expediency, I will bypass going into too much detail on this, but the section “Natural Resources and Civil War” in the 2003 essay “Economics and Violent Conflict” is worthy of future investigation.

As far as China and a possible conflict, the indicators as listed above are disturbingly plausible. As of 2019, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ “Food Security Snapshot” provides some reassurance on China’s crop projections and trends – the only points of minor concern noted were cereal (wheat) requirements as well as an ongoing problem with African Swine Fever.

Economically, however, China – as with the rest of the world – has entered uncharted territory. Despite U.S. tariffs on products made in China, their overall growth (GDP) remains positive, though slightly slowed. The current global surplus of oil negates any critical imperative to aggressively push for exploitation of the South China Sea, while the sudden global slowdown in the demand for consumer goods might provide a strain on the Chinese economy over the next year. However, these factors suggest that the situation – at the moment – is not critical.

Domestically, the justification of a conflict initiated by China is similarly problematic. Aside from defensive posturing over the long-contested South China Sea, the idea that overt Chinese aggression could be somehow rationalized without internal repercussions is difficult to consider.

The great variable, of course, is the courses of action of both the virus and the global reaction to the pandemic. A more pronounced resurgence/a successful containment… a resilient global economy/a catastrophic and cascading series of economic failures… magnanimous cooperation/increased paranoia and distrust… Three months ago, no one had any idea we would be where we are at the moment; three months from now any guess is as good as the next as to where we might be.

“What prevents war?”

As I was writing the above, I realized that I was progressively answering much of this additional question. However, there is no real prescription for the ailment which has vexed mankind throughout its existence – the desire to fight.

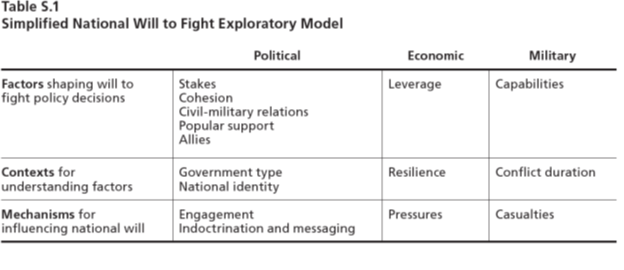

Returning to the RAND study, there is a figure which might serve as a guideline on what factors might be effective if they are removed or negated:

For example, if the political stakes are too high, the economic resilience would not support the conflict, or the threat of civilian and military casualties threatens not just the immediate capacity for conflict but the follow-on restructuring, then war might not be the best course.

While this is painfully obvious and simplistic, one of the key findings following this table in the report is equally simple and (somewhat) amusing:

Comprehensive, rigorous examinations of national will to fight as a concept, however, are severely lacking. Most importantly, efforts to apply that concept to contemporary conflict scenarios are also lacking. (page xiii)

“What next?”

I have no idea.

What I do know is that my insatiable curiosity to see how this all pans out tends to overrule much of my own dread at the prospect of facing such huge unknowns.

…That, and the fact that all of this is great fodder for my own amateur speculations and observations.

Discover more from milsurpwriter

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Three Questions – No Answers… Yet”